An Indigenous Alternative to the Western Apocalypse in Uma História de Amor e Fúria

By Max Vetter

Any cursory glance at the American apocalypse film quickly yields the image of a genre either unaware or unwilling to reckon with the reality that it is treading familiar ground. Like any historical, horror, or fantasy film, the apocalypse film is never strictly about its constructed world but rather abstracts contemporary fears and conflicts to make them more palatable. However, what’s curious about the American apocalypse film is how often the central conceit of an apocalypse film goes unaddressed. Namely, you can only worry about the end of the world if it hasn’t already ended.

This is to say that while the American Empire is one which can fantasize about the myriad ways it could topple, the ways it does so are often mirrored by the actual atrocities it has committed against the many millions of Indigenous people whose land it now occupies. With that said, instead of zeroing in on how Hollywood has whitewashed the historical and ongoing apocalypses of Indigenous peoples, I’d like to take a small look into the rich, burgeoning world of Indigenous Apocalypse Cinema, highlighting Luiz Bolognesi’s radical Uma História de Amor e Fúria (2013).

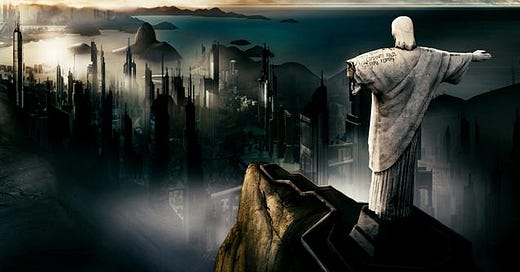

Uma História de Amor e Fúria follows the life and reincarnations of Abeguar, a warrior of the Tupinambá tribe granted the gift of flight, and Janaína, his beloved who is killed during the hostile colonization of Brazil by the Portuguese. The film has four segments spanning more than 500 years of Brazilian history. Guanabara, 1566; just at the dawn of Portugal’s decimation of the Tupinambá people. Maranhão, 1825; Brazil having recently claimed its independence but still enforcing a brutal slave trade. Rio, 1968; an autocratic military dictatorship suppresses the dissent of a growing student movement. Finally, Rio, 2096; in a stratified Rio where water is more valuable than gold, the lower classes are forced to drink salt water while the rich hoard enough fresh water to populate aquariums of indigenous fish. In each time period, Abeguar, unable to use his powers, finds a reincarnation of Janaína, unaware of her identity, and the two fall in love only to be ripped apart again in the fight against systemic oppression.

The cyclical nature of the movie does a few things here, but most importantly, it creates a textual connection between all types of colonial violence, and demonstrates how all of them are echoes of the foundational genocide of Indigenous peoples the West was built off of. At the same time, extrapolating this violence into the far future allows the film to argue that we either need to address the current injustices befalling Indigenous communities—ethnic cleansing, seizure of land, and forfeiture of rights—to prevent the future presented in the film, or accept that if we don’t then the societal corruption and collapse we face will be a reflection of the violence which founded said society. The ways that the Rio of 2096 function have direct parallels to each of the systemic injustices the film spotlights in the previous three segments.

The first, most obvious one is the desecration of the land; much like the Portuguese conquerors of the 1500s, the industrialists and capitalists of this city not only destroy the land and pollute the water, but make it systematically impossible for those who it belongs to to access it while themselves monopolizing it for profit. The city is organized vertically, making literal the class disparities which mirror the equally rigid hierarchy of 1800s slavery. Additionally, like the Silva regime in the 1968 segment of the film, Rio 2096 is run by an oppressive police state who keep it “one of the safest cities in the world” by punishing even the act of children playing with a ball with death. In this way the film argues that if the structures of colonialism and imperialism are not stopped, then they will simply employ the same tactics into the foreseeable future.

Despite the grim and explicit reflection of Indigenous trauma Uma História de Amor e Fúria presents in its apocalypse, it also uses Indigeneity to propose a solution to said problem. Abeguar and Janaína go through parallel arcs in the film, their romance acting as a metaphor for the intersection between two forms of liberation through Indigeneity: tradition and identity. Abeguar can be seen as a manifestation of tradition, given his status as a powerful warrior with highly culturally coded abilities. However, his flaw is that, while he is able to use his heritage to escape death through reincarnation, he is unable to use his powers to help in the fight against oppression. On the other hand, Janaína, being introduced wearing the pelt of a jaguar, a culturally coded symbol, can be seen as a manifestation of identity. Janaína’s flaw is that she, unlike Abeguar, does not remember who she was in each reincarnation, which condemns her to make the same mistakes each time she dies.

What the film calls for, then, is not only an embrace of these two facets of Indigenous identity—through Abeguar finding the courage to once more unlock his powers of flight and through Janaína embracing her identity and becoming a full-blown guerrilla by the last segment—but an acknowledgement that both of these things must work in tandem for Indigenous peoples to free themselves from the shackles of colonial rule. Through Abeguar and Janaína’s eternal romance, one continually thwarted by repressive violence but ultimately consummated time and time again in the face of evil, the film leaves with an ultimately hopeful message. While the violence of colonialism is brutal and cyclical, while resistance to it will always be necessary and difficult, if not just the Tupinambá and other native American groups, but Indians, Armenians, Congolese, Irish, Palestinians, and all the other oppressed Indigenous communities of the world love each other, love their traditions, love their identities, then they will have the strength to heal from the apocalypses they’ve endured and stop the apocalypses yet to come.